And Pax Mongolica Broke Out

All Across the Land

Peace as a Consequence of War

After Temujin (Genghis Khan) unified the steppe tribes to create the Mongol Empire in the year 1206 AD, he set out to expand its territory. Marriage alliances, as discussed here, were one such strategy, but military conquest is best known in the West. Payoffs were big. Risks were big, too, but the Emperor (the honorific bestowed upon the khan as laid out in this past column) was a master at organizing his commanders, soldiers and their households into ruthless, highly effective armies.

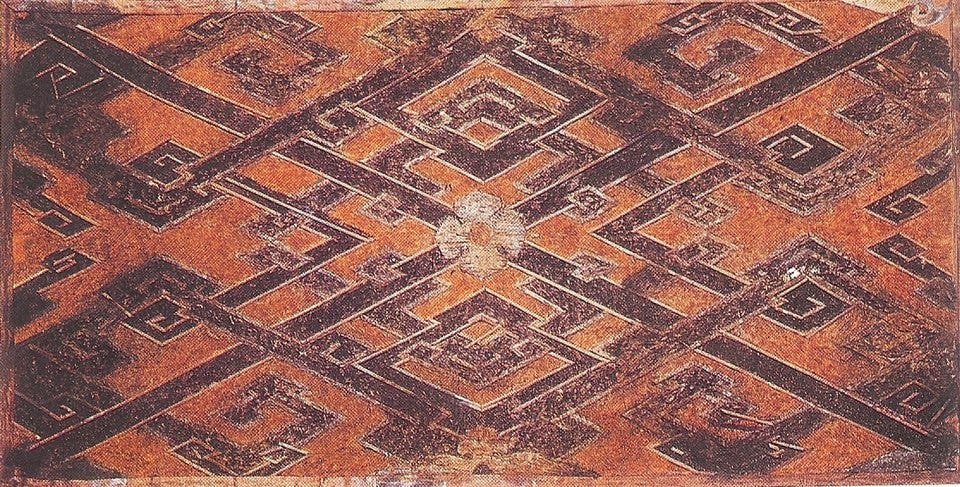

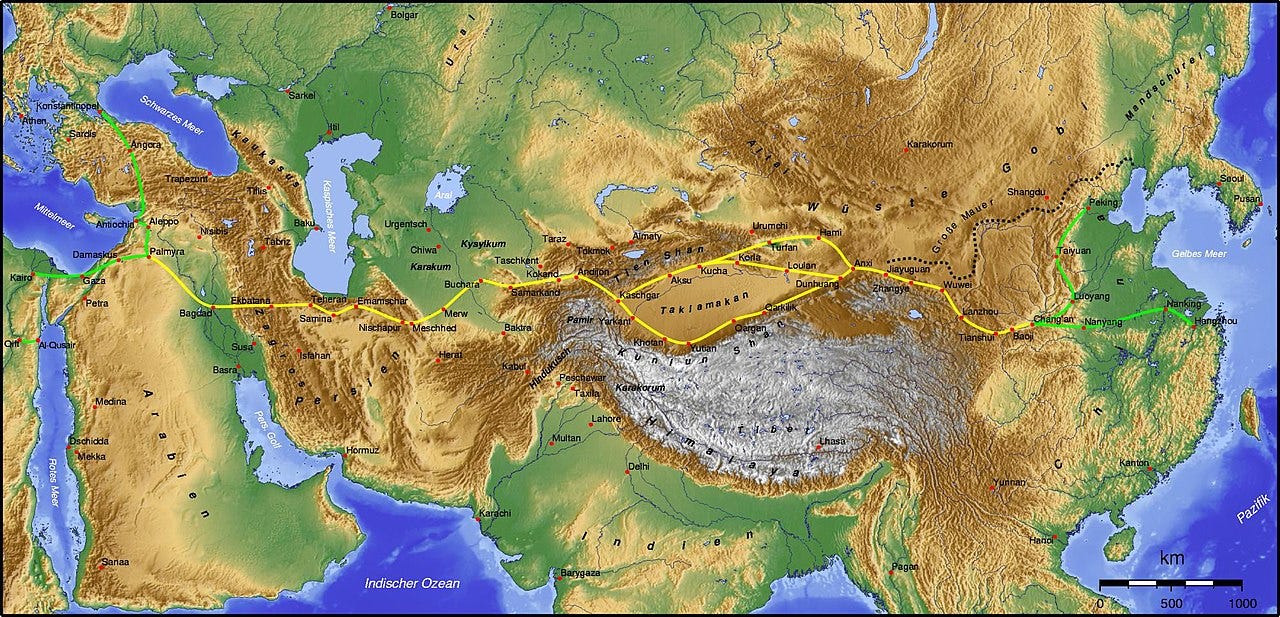

Key to this expansion lay in control of the Silk Roads, located within the empire’s immediate reach. These trade routes, ancient even in the 13th century, stretched four thousand miles in a network from Dadu (Beijing) west to the Middle Sea (the Mediterranean) and beyond. Whoever controlled the trade routes controlled, effectively, most of the known world—its lands, its people and its considerable wealth.

Tempting, then, for a nascent tyrant who knew all too well the grim fate of anyone who fell prey to enemy forces. For decades, Temujin had suffered brutal oppression at the hand of his steppe overlords. He dared to challenge the prevailing order, and he came out on top. Perhaps for this reason he made the choice to keep going. He went to war again. Genghis Khan became hunter rather than hunted; conqueror rather than conquered; ruler rather than oppressed peasant.

But his ferocious land grab was accompanied by an unexpected consequence. Peace broke out. This period of peace is known today as Pax Mongolica. Pax Mongolica brought unprecedented prosperity and security to Central and Eastern Asia. How did this happen?

As the khan built his empire, he set up military outposts every twenty or thirty miles along the Silk Roads — the distance a rider could travel before needing to switch mounts. Later, the system was expanded by Genghis Khan’s son and successor, Ogedei Khan. This network was called the yam. These yam outposts provided fresh horses, fodder and riders. This medieval pony-express style system enabled messages to travel with much greater speed, a necessity in a rapidly growing empire. Thus, the military presence had the benefit of making the Silk Roads safe for decent, law-abiding people. While the Mongols were in power, it was said, a virgin with a nugget of gold carried on her head could walk unmolested its entire length.

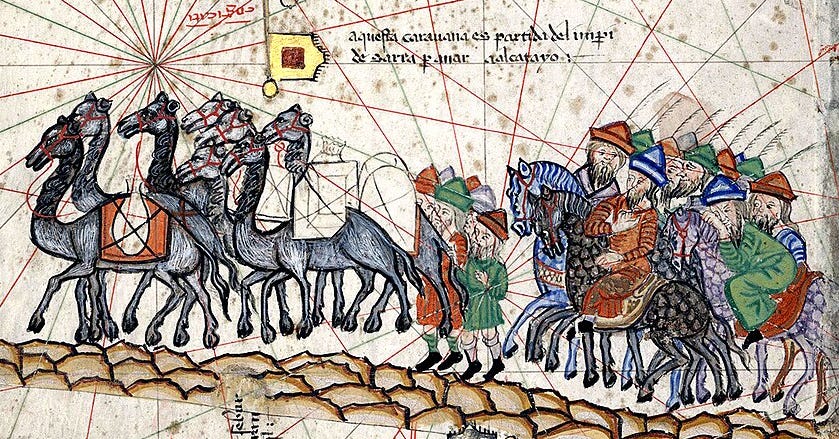

One result of this was an explosion in the size of the merchant class. Traders plied their goods along local routes that stretched in an unbroken chain from China to Europe. Some became rich. Very rich. Explorers, tourists, pilgrims, missionaries - people of all classes, and from all walks of life spread languages, customs, scientific discoveries and faiths from one end of the known world to the other.

It was Pax Mongolica joining East with West via the span of the Silk Roads that enabled Marco Polo, William of Rubruck and other Europeans to travel to and report on the Mongol royals, its court and its people. Because of Pax Mongolica we have Western eyewitness descriptions of Central Asia, the Mongol capital of Karakoram, and later Khanbaliq, also known as Dadu (predecessor to Beijing), capital of the Yuan dynasty, and the magnificent court of the Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan.

Family infighting and the Black Death were among the causes that broke up the empire and brought an end to Pax Mongolica. But for a time, Genghis Khan and his successors brought about a measure of peace and stability in the region that today’s leaders might envy.

Of course, modern armies don’t lay siege to exotic cities or enslave their artists, scholars and engineers. And it took a khan with the genius of Temujin to be able to effectively govern what would become history’s largest contiguous empire. Although he faced an unimaginable array of administrative challenges, what might have descended into a clash of civilizations instead coalesced into Pax Mongolica, and a cosmopolitan court extolled far and wide as a center of learning, of science and technology, and of religious tolerance.