Genghis Khan's 'aha' Moment, Part II

A Mongol Origin Story Composed as Epic Poem

Before the rise of Genghis Khan, the Mongols lacked a system of writing. This left them without a recorded history or body of literature; a state common to nomadic people. Because of this, the world has been deprived of knowledge about the governance, social structure and worship practices of mobile societies, the Mongols in particular. Yet, the man called by the Washington Post as ‘The Man of the Millennium” saw fit to provide his nation with a means to write down their distinct oral heritage.

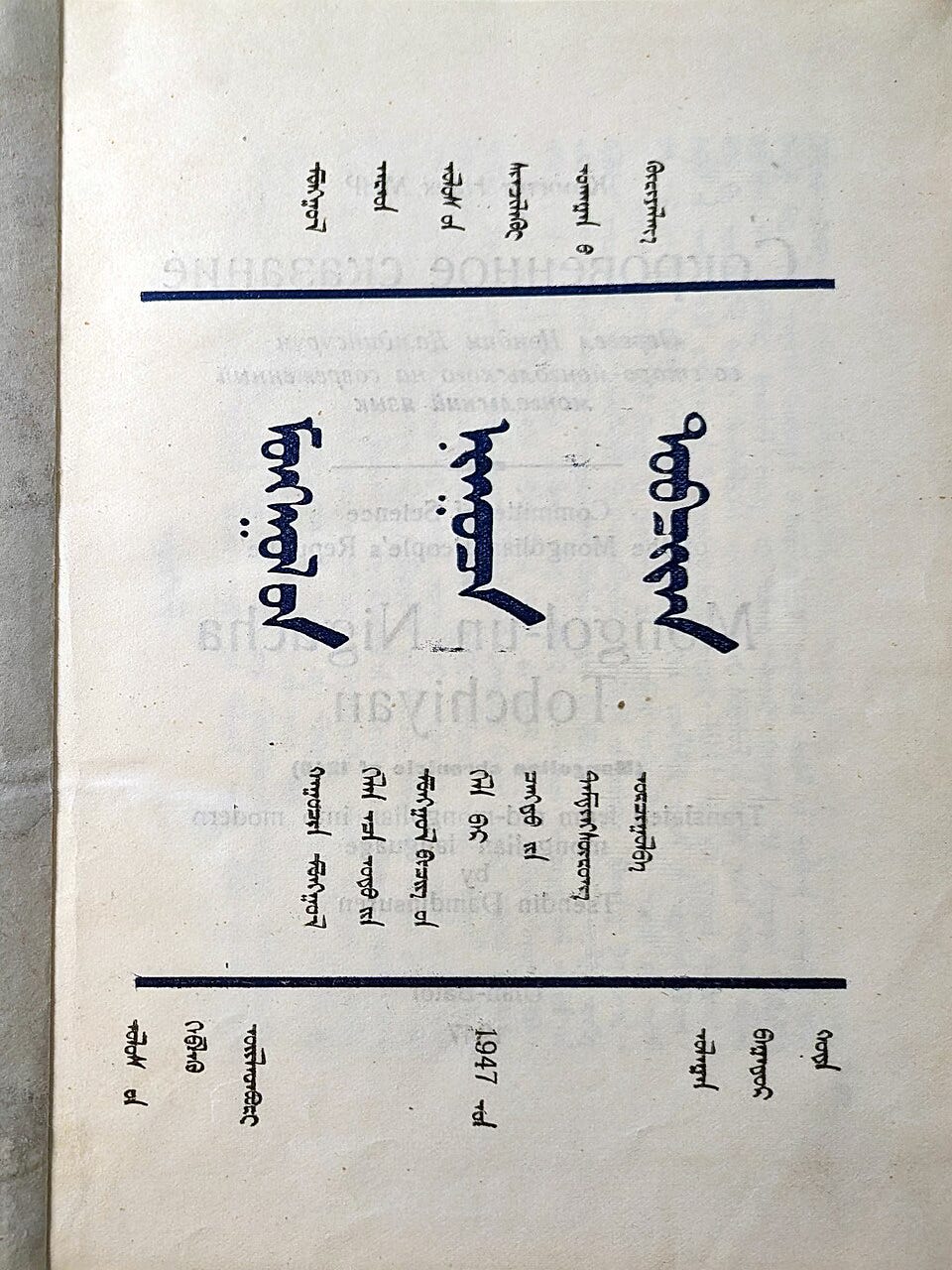

After his death in 1227, an unknown author used the newly invented Mongol alphabet and composed an origin story of Genghis Khan and his clan, the Borjigin Mongols. The work was likely commissioned by the Mongol royal family and its author is thought to have been an intimate associate. The document is known as “The Secret History of the Mongols.” It is the only known contemporaneous eyewitness account of the origins, life and rise of Genghis Khan.

The story is composed as an epic poem and begins with the mythic origins of Temujin. The legend tells of a Blue Wolf mating with a White Doe, from which came the first Mongol, named Batachiqan. Eleven generations later, a widow, Alan Gua the Fair, conceived three sons by a supernatural being who entered her ger through its top. The youngest of the sons was Bodunchar, founding patriarch of the Borjigin clan, of which Temujin was a member. Borjigin leadership continued to provide rulers for Mongolia until the twentieth century.

Historians generally agree the greatest value of Secret History lies in its detailed chronicle of Mongol life in the 12th and 13th centuries. In addition to the empire’s military organization, Secret History provides a picture of its nomadic life, social structure and culture during that period of transition from federation of clans to empire. It depicts Temujin as a charismatic leader who inspires his people to act on his vision of achieving dominance over the steppe in the face of overwhelming odds.

Its historic accuracy is more controversial, with some scholars calling it a blend of fact and fiction, with fact nearly impossible to separate from fiction. Indeed, part fact, part fiction and part legend merge in my upcoming book that chronicles the rise of Borte and Genghis Khan. Fact, fiction and legend can be, and is also, applied to “The Secret History of the Mongols.”

There are many reasons Temujin might have been motivated to order a written language for his people. As the mobile Mongols increasingly encountered the sedentary world, a written system for their language made more and more sense. Governance, ease of communication, and efficiency must have all played a role in its creation and implementation. And not a small part of this desire by Temujin might have been the legacy he wished to leave. In his later years, he actively sought an elixir for immortality:

In the end, denied his rather poignant quest for eternal life, the Emperor departed this life unaware that his triumphs and deeds would lead to the world’s largest land empire in human history. But did he? After all, we have vague suppositions as to the Secret History’s author; but the commissioner of the work is, to date, silent to history. It remains entirely possible he discussed such a desire with his family and trusted advisers.

Temujin could not have known the impact on the world of his written language. But without it, history would be bereft of knowledge of the Mongol heritage, the toughness and resourcefulness of her people, and the life of the man who guided them to unimaginable, if ignominious, greatness. Thanks to that unknown scribe, The Secret History of the Mongols lives with us today, a testament to a man who very nearly conquered the world.

This is a fascinating history. This is one of many pieces of your story that I think have been lost to ignorance. I love that you are bringing this back to life.