How Khutulun Became Turandot

To her, Genghis Khan was 'Granddaddy'

Plus, a little fun with Grok

My most recent research into the Mongol Empire has taken some curious detours. Inconvenient, awkward, and plain old strange bits of history keep popping up in my internet searches that simply don’t fit our notions of Genghis Khan, Borte and the Empire. In fact, it’s such an odd phenomenon that I’m compelled to write about it.

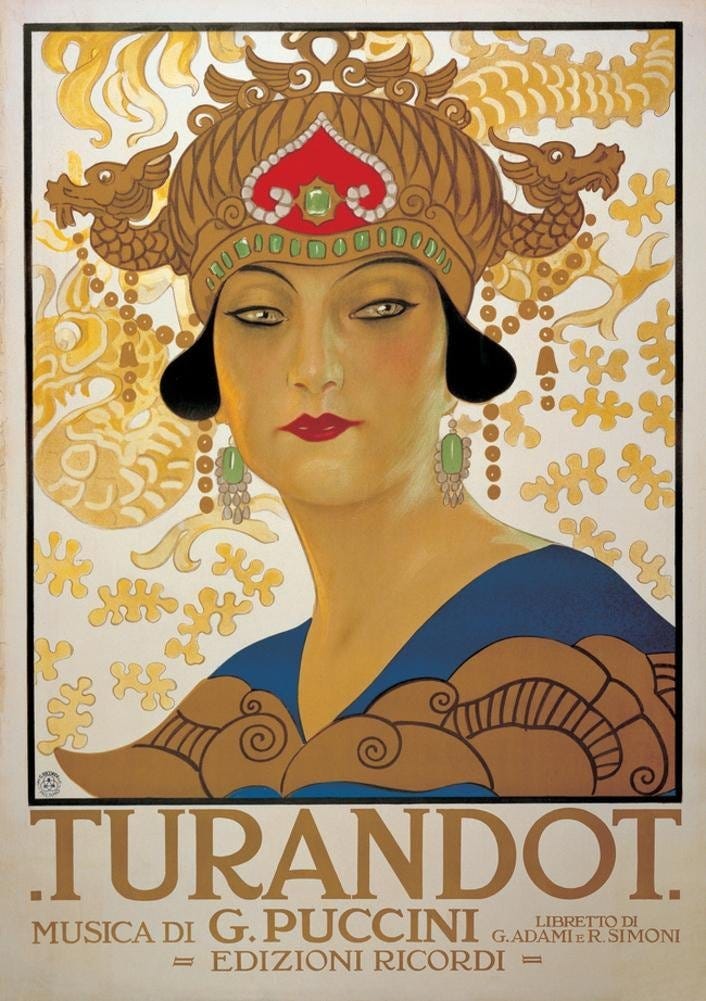

The striking image above is the cover art for the score of the great Puccini opera “Turandot.” The artist who created it was Leopoldo Metlicovitz, an Italian. Turandot, in case you’re wondering, is the name of the Chinese princess featured in said opera. In the story, the Princess Turandot refuses to marry, going so far as to execute any suitor unable to solve three riddles she puts to them.

A clever prince solves the riddles, but Princess Turandot is loathe to marry him. How does the story end? You’ll have to watch the production to find out. Or, an AI or other internet source will be happy to give you a quick, one-minute plot summary. In the clip of the finale I’ve pasted below, everyone is smiling and the lighting is lustrous and gleaming, so that should give you some clue.

Curiously, though, how does Turandot refer to a historic character named Khutulun, and thence to Genghis Khan, you ask? Sit down, and I shall tell you.

In history, Khutulun was a great-great-granddaughter of Genghis Khan himself. Born near the year 1260, and long after the tyrant’s death, Khutulun was renowned for her abilities in horsemanship, archery and, especially, wrestling. Given that wrestling is the premier sport of the nation of Mongolia, Khutulun’s talent won her much acclaim, especially since no man was able to defeat her. Indeed, she out-wrestled numerous elite Mongol warriors. Below, I’ve pasted an artist’s rendition of what he imagined Khutulun, or Turandot, to look like. h/t Jack Weatherford

It was Marco Polo, among others, who wrote of his encounter with Khutulun and her exploits in his book “The Travels of Marco Polo.” Khutulun refused to marry any man she defeated in wrestling, and required him to wager his best horses in order for a chance to win her. If she defeated him, the horses belonged to her. In Marco Polo’s account, Khutulun is never defeated; thus, she never marries. When she died, it is said she owned over 10,000 fine steeds.

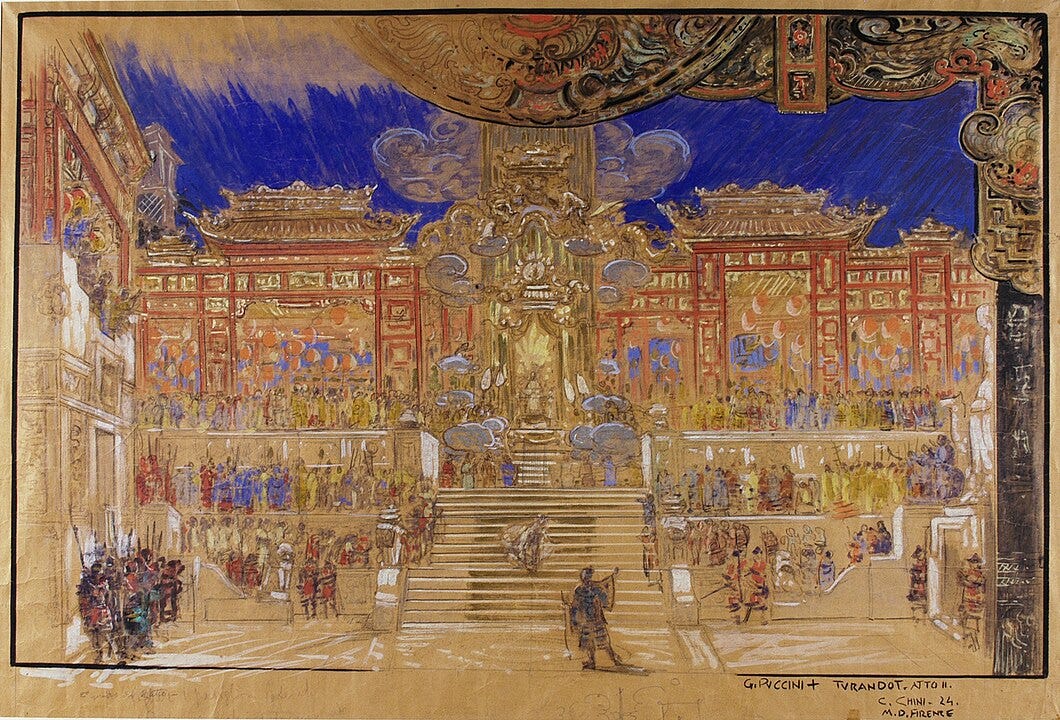

If you care to see a sampling of this grand stage production, taken from last October’s dress rehearsal, here is a portion of the finale, sung by Angela Meade and the Met Chorus of the Metropolitan Opera.

One of the several encounters we have of Khutulun in the West comes from a multivolume collection of legends and fairy tales published between 1710 and 1712 entitled The Thousand and One Days. The author and orientalist, Francois Petis de la Croix, based one of his stories on the historic character Khutulun. It would be certain that de la Croix was familiar with the works of M. Polo and likely drew his story from those accounts. De la Croix calls his princess, Turandot — which means daughter of Central Asia, in Persian — and instead of horses, her suitors are required to wager their heads in exchange for the chance to answer three riddles and thus win her hand in marriage.

Some decades later, de la Croix’s story was adapted into a stage play and from that, a German language version was written, entitled “Turandot, Princess of China,” and performed in 1801. It was, supposedly, this latest take on the legend that inspired Puccini’s opera.

I plan to write more about odd Western cultural takes on the Mongol Empire in future posts. In the meantime, here is a screenshot of a partial Q&A I had with an AI for some information and context of the image up top while I was writing this post. With Grok, from X: