The Power of Ten

Temujin has a problem. It’s the kind of problem that we in the West, given another eight hundred years will be called ‘a good problem to have.’ It is the Year of the Tiger (1206AD for us), and ground-dwelling peasant Temujin has spent the past two decades battling the oppressive steppe aristocracy. His goal? To unite the clannish, warring steppe Mongols beneath a single spirit banner.

He is now the undisputed leader of a new nation, a nation many times the size of his original tribe of Borjigin Mongols. He takes the name Genghis Khan, which has been translated to such things as “khan over all,” “khan of all between the oceans,” “universal ruler.” And so on.

In addition to the now loyal Mongol clans, other defeated tribes and nations have fallen under Mongol control, the Kerait and Naiman among them. Some of these nations are enemies of the Mongols. And therein lies Temujin’s problem. The numbers are so great they threaten to overwhelm the Mongols, rise up against Temujin and thence destroy the newly formed nation.

How to govern such large numbers? How to win the loyalty of the hostile bands? How to avoid mass revolt and revolution?

He restructures Mongol society into military units based on decimals of ten. Every male between 15 and 70, the ages considered suitable for military service, is assigned to a minqan (pl. minkad), or group of one thousand soldiers. The minqan is divided into ten jaghun (pl. jaghat), or ten groups of one hundred. From there, the jaghun is divided into groups of ten soldiers each, or arban (pl. arbat). In addition, ten minqan are grouped to form one tumen, or a single group of ten thousand soldiers.

Captured soldiers from the conquered tribes are separated from their compatriots and distributed among the various units. This breaks clan ties and ensures loyalty to the Mongol nation and specifically Temujin, thereby minimizing the risk of uprising and revolt.

Each soldier brings to his assigned unit his entire household—wives and their children, herds, horses, wagons and equipment. These provide necessary supplying and logistical support. Timothy May, professor of Central Eurasian history at University of North Georgia, terms this a ‘military industrial complex,’ which, now that I consider it, seems to fit.

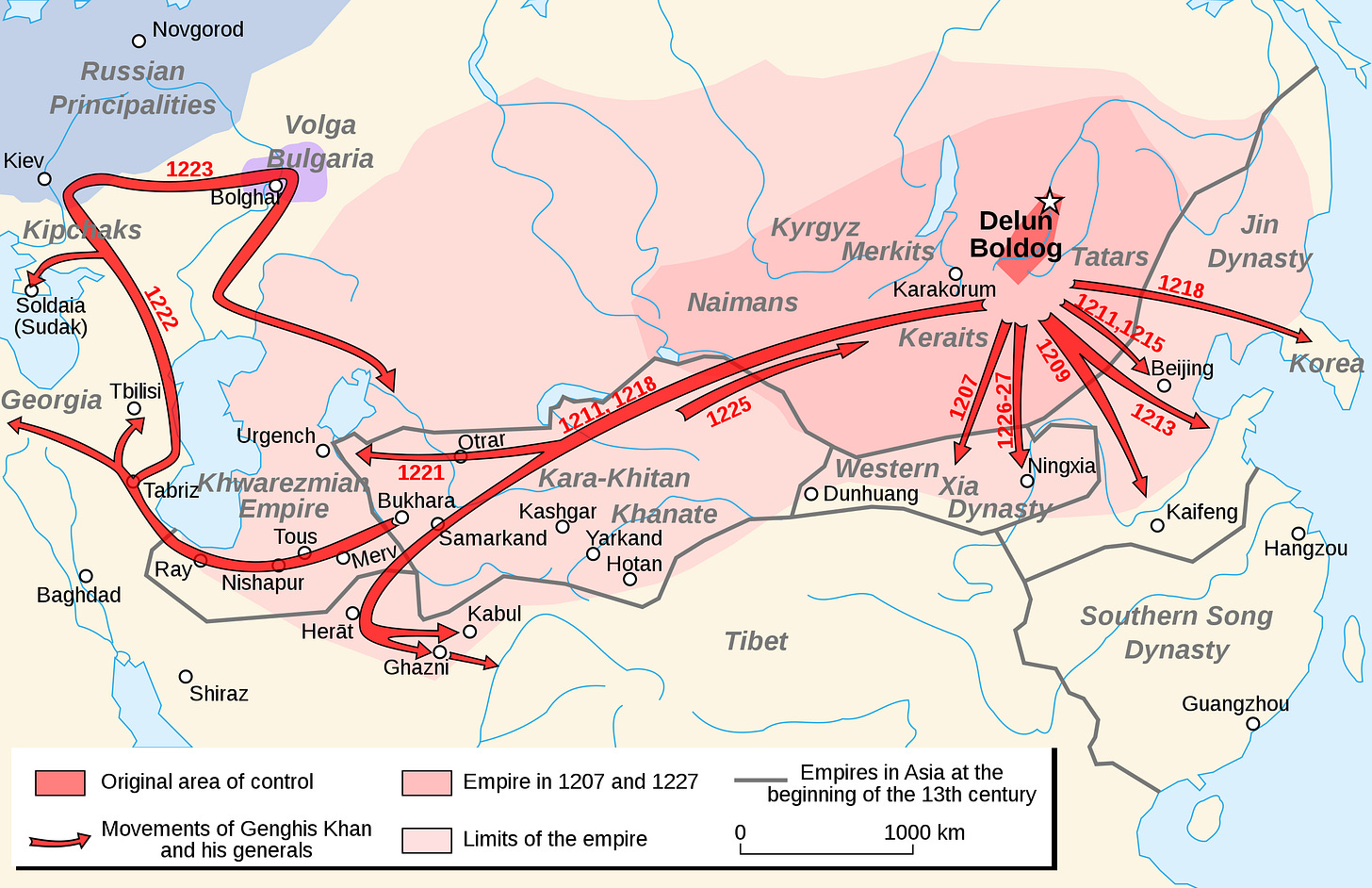

Having secured the steppe, Temujin, now Chinggis Khan, turns his energies to maintaining his rule. This is done partially through marriage alliances—he takes numerous wives and makes strategic matches for his daughters that ensure geographic advantage for his Mongol nation. He takes control of Siberian trade and mining operations, then sends armies west into Central Asia and south and east into China. The conquest for empire has begun. Below: Empire, 1207-1227 (year of the khan’s death)

He certainly turned that problem into a huge win!