Ties that Bind: Genghis, Oranges and Me

Citrus almost certainly migrated to Europe from China over the Silk Roads. I say “roads” because the ancient trade routes over which those fruits traveled necessarily diverged at mountain ranges and deserts, creating two main, North and South, branches. Over the millenia, many other routes emerged and were added to the network.

My purpose with this post is to connect some dots for readers in my journey of writing not one but four books featuring the Silk Roads of the Middle Ages, with Genghis Khan and his progeny in roles of varying import. But back to citrus - oranges in particular, both the fruit and the book. The author John McPhee once wrote an article for The New Yorker entitled “Oranges,” which later became a book. “Oranges” was as fascinating a McPhee read as anything by him I had ever read, and it was “Oranges,” the book, that started me on my medieval Silk Roads journey. McPhee writes, and I’m grossly paraphrasing here, that when the Normans began their rule of Sicily late in the 11th century, they found a royal court laden with sensual Arabic indulgences - emirs in flowing robes of linen and silk, harems of almost limitless variety and, yes, oranges. Perhaps most importantly - but who knows, with all those harem girls - oranges.

In addition to the exquisite fragrance of the orange blossoms, the Sicilian air was likely perfumed with scents of jasmine and rose, too. The possibilities of the time and place invaded my modern senses just as the heady Arab influences must have invaded Mediterranean culture a thousand years ago. My curiosity piqued, I dove down the rabbit hole of Norman Sicily and the trade routes connecting it to the rest of the world. Silk manufacturing came to Europe from China via smuggled mulberry seeds, a death sentence if discovered; missionaries brought Christianity and Buddhism to the Far East; and endless caravans of people, animals and goods stretched, impossibly, for five thousand miles and thousands of years before the birth of Christ. What? How could this be?

Further research brought to light the fact that spies from the armies of Batu Khan, grandson and successor of the world’s greatest conqueror himself, were spotted in Venice in about 1240 AD. From there it was no jump at all to link Europe with China in that era, especially given the thousands of years of travel over the trade routes. If Mongols came to Europe in the 1200s, then certainly Europeans could travel to China. (And they did, by the way. Headstones from the 1300s found in China have identified an Italian silk merchant family who lived there. It's not the 1200s, but it's close enough.)

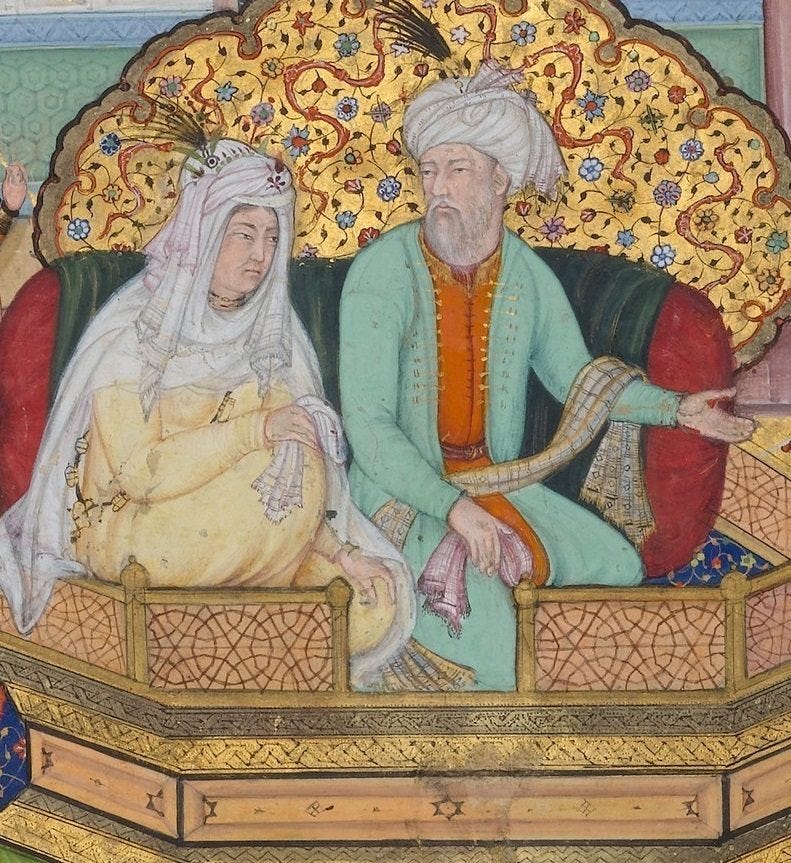

Outlines and character studies eventually morphed into a medieval romance trilogy that takes place along the Silk Roads, along with a fourth book, an epic about the rise of the Mongol nation under Genghis Khan, featuring his principal wife, Borte. Borte, though written records are scarce, is known and loved in the story of the Mongol Empire. She went to war, sacrificed, birthed and raised eight children, ruled their burgeoning khanate in her husband’s absence, and so much more during their forty-plus year marriage.

With the time and place firmly ensconced in my being, inspiration drove me to write the book. It advanced into the quarterfinals of Amazon’s Breakout Novel contest with over ten thousand entries. And now, finally, it will soon be published.

So, that is my tale of how Borte and the book Empire came to be, and my inspiration for a historical romance trilogy that takes place in some of the oldest and most exotic locales on earth. Come along on the journey for some fascinating insight into history’s fabulous tales as we travel back in time along the ancient trade routes known as the Silk Roads.

The pictures with this are so cool!